Response to Carol Schmidt's December 13, 2023 letter to the Peninsula Pulse

Dear Carol Schmidt,

I saw your letter at https://doorcountypulse.com/letter-to-the-editor-love-thy-neighbor-has-no-except-after-it/.

You write at the closing,

Love thy neighbor as thyself. Remember, there is no “except” after this commandment.

The command to love your neighbor is in different Bible passages, so the puzzle this gives me is, which one are you referring to?

It is possible you were drawing off of Leviticus 19, especially verses 18 and 37: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Leviticus+19&version=KJV

The command is also in Matthew 22 and Mark 12:

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew+22&version=KJV

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Mark+12&version=KJV

Since you don’t mention the first of the two commandments, and earlier in your letter you reject that there “is only one true way”, it seems less likely that you were drawing from the Gospels. The first of the two commandments reflects the demand for God be worshipped exclusively rather than in combination with idols. It is a quote from Deuteronomy 6, verse 5: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Deuteronomy%206&version=KJV

The commandment is also cited by St. Paul in his letter to the Galatians: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Galatians+5&version=KJV

This fits the first of your sentences, but not the second. Also, in Galatians, the command is followed by a list of sins related to the purity of life and devotion, with the condemnation that “they which do such things shall not inherit the kingdom of God”. This likewise goes against your rejection of there being only one true way.

So it is most likely you were drawing off of the Leviticus passage, since the parts surrounding the commands to love your neighbor and to observe all of God’s statutes without exception partly includes laws of a civil or ceremonial nature, and it is a listing of various laws rather than a narrative.

Perhaps you would rather consider any inconvenient parts as being either civil or ceremonial rather than morally binding?

Yet even then, in one of your past letters, https://doorcountypulse.com/letter-to-the-editor-and-so-it-goes-2/ you complain:

Meanwhile, we have… bans on what we can do with our bodies. I wonder when “we the people” will wake up and realize that the Republicans’ main platform amounts to fear and money and power for them. Where is the sanctity of life? Is it only when they control another person’s body?

So you have an exception to loving your neighbor, since protecting unborn babies under the law is unacceptable to you. Babies don’t become your neighbor only the moment they are born, and their own bodies are growing prior to birth. Recognizing and protecting babies even before birth, such as how Joseph and Elizabeth did, can be part of “love for family” and therefore part of the meaning of Christmas which you have discovered so far.

Since you have shared with me the what you have found about the true meaning of Christmas, let me share with you about the true meaning of Door County’s name. As you already know, it starts with the passage way, named in French.

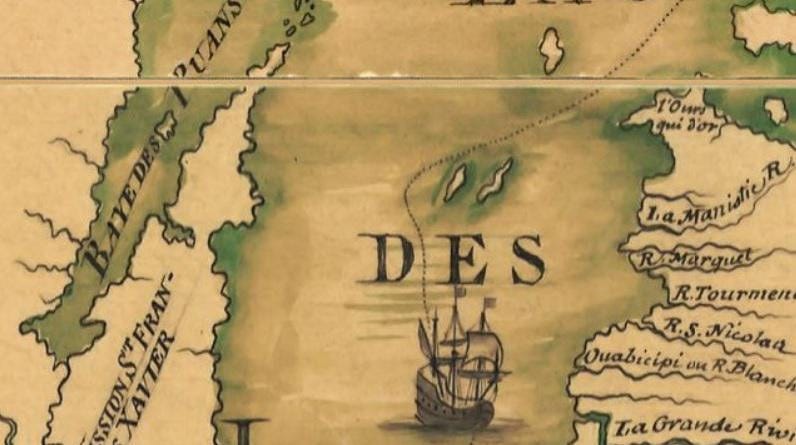

Part of an 1849 map, cropped to show “Port du Morts” in the center. Like with “Sturgeon Bay” and “White Rapids”, the text is angled to show the orientation. The map is courtesy of the Northern Illinois University Digital Library.

https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-twain%3A10499/

The map is labeled “Porte du Morts” instead of “Porte des Morts”. “Du” means “of” and “des” is “of the”. The difference between “Port du Morts” and “Porte des Morts” is small; it is the difference between “Door of Death” and “Door of the Dead”.

This is an interesting name, and it comes with a pre-existing set of associations. A look into this can be seen in a 17th century French dictionary, which has entries for “the Doors to Life” and “the Doors of Death” next to each other.

This dictionary, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Le_Dictionnaire_Chretien_Ou_Sur_Differen/gjViAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA660&printsec=frontcover, was written by a scholar of the Church Fathers who was for a time imprisoned for Jansenism. A biography of his life: https://fr-m-wikipedia-org.translate.goog/wiki/Nicolas_Fontaine_(%C3%A9crivain)?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en&_x_tr_pto=wapp

Each original language quote has English thanks to Google translate, in some cases improved slightly. The entry for “Les portes dé la vie”:

Les portes dé la vie dont parle l'Ecriture, font le renoncement au monde, & la conversion vers Dieu, c'est la charité & la chasteté par lesquelles l ame aime un seul & vrai Dieu. Les portes de la vie, sont encore les saints exercices de pieté.

The doors to life of which Scripture speaks are renunciation of the world, and conversion towards God, it is charity and chastity by which the soul loves the one and true God. The gates of life are even the holy exercises of piety.

Now the entry for “Les portes de la mort”:

Les portes de la mort, font les fens du corps. L'Ecriture dit clle même, que la mort eft entrée par nos fenestres. Mors intravit per fenestras. Les portes de la mort, sont encore les mauvais desirs, par lesquels on en tre dans la mort. On est entré tout à fait quand on jouit de ces desirs.

The doors of death are the walls of the body. Scripture itself says that death entered through our windows. Mors intravit per fenestras. The gates of death are still the evil desires, by which one enters into death. We have entered completely when we enjoy these desires.

“Mors intravit per fenestras” is in italics, and is shortened from a larger quote, “Mors intravit per fenestras vestras” in Latin, which is from a letter Jerome wrote to Julia Eustochium, his patron’s daughter:

patrem tuum, veniet et pulsabit et dicet: ‘Ecce ego sto ante ianuam et pulso. Si quis mihi aperuerit, intrabo et cenabo cum eo et ipse mecum,’ et tu statim sollicita respondebis: ‘Vox fratruelis mei pulsantis: aperi mihi, soror mea, proxima mea, columba mea, perfecta mea.’ Nec est, quod dicas: ‘Dispoliavi me tunicam meam, quomodo induar eam? Lavi pedes meos, quomodo inquinabo eos? ’ Ilico surge et aperi, ne te remorante pertranseat et postea conqueraris dicens: ‘Aperui fratrueli meo, fratruelis meus pertransiit.’ Quid enim necesse est, ut cordis tui ostia clausa sint sponso? Aperiantur Christo, claudantur diabolo secundum illud: ‘Si spiritus potestatem habentis ascenderit super te, locum ne dederis ei’ Danihel in cenaculo suo—neque enim manere poterat in humili—fenestras ad Hierusalem apertas habuit: te tu habeto fenestras apertas, sed unde lumen introeat, unde videas civitatem Dei. Ne aperias illas fenestras, de quibus dicitur: ‘Mors intravit per fenestras vestras.’

your Father, he will come and knock and say: 'Behold, I stand before the door and knock. If anyone opens the door to me, I will go in and dine with him, and he with me,' and you will immediately answer anxiously: 'The voice of my brother knocking: open to me, my sister, my neighbor, my dove, my perfect one.' Nor is it that you should say: 'I have stripped myself of my coat, how shall I put it on? I wash my feet, how shall I defile them?' Get up at once and open, so that He does not walk away, leaving you in remorse, and later you complain, saying: 'I opened for my brother, my brother walked away.' For what is necessary, that the doors of your heart are closed to your spouse? Let them be opened to Christ, and shut to the devil according to the saying: 'If a spirit having power ascends upon you, don't give Daniel a place in his upper room - for he couldn't stay in the low one - he had the windows open to Jerusalem: you have your windows open, but from where the light may enter, whence you may see the city of God. Do not open those windows, of which it is said: 'Death entered through your windows.'

https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2008.01.0566%3Aletter%3D22

This is a cryptic string of thoughts, which are untangled by a commentator at https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0a2a/143bd22702f423a12261c596c9e2ae380e04.pdf#page=14.

Jerome’s phrase, “Death entered through your windows” is an alternate translation or informal paraphrase of Jeremiah 9:21, a lamentation that the daughters of Zion are to learn in order to mourn for the coming exile. In the link above, it is mistakenly identified as verse 24, but it is really verse 21, which in the Vulgate is

quia ascendit mors per fenestras nostras; ingressa est domos nostras, disperdere parvulos deforis, juvenes de plateis.

because death has come up through our windows; she entered our houses, scattered the little ones outside, the young people from the streets.

The difference in the Vulgate, “ascendit” as opposed to “intravit” in the italicized phrase, is the difference between “climbed” and “entered” according to Google translate. So it isn’t much of a difference.

A difference between the 17th century understanding and the modern sense of “death’s door” as in “knocking on death’s door” is that the older use implies guilt. The older phrase does not just reference a proximity to death, but also a falling for evil desires which merit death. This relates to the first part of Romans 6, verse 23:

For the wages of sin is death; but the gift of God is eternal life through Jesus Christ our Lord.

But the French phrase seems to go beyond sin meriting death in an overall sense. Rather, one or more particular faults are at work. So by calling it Porte des Morts or Port du Morts, the French were associating it with guilt.

Similarly, in his retelling Hjalmar R. Holand attributes it to arrogance: https://www.google.com/books/edition/History_of_Door_County_Wisconsin_the_Cou/zFo0AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA38&printsec=frontcover

The question can be raised whether it was fair of the French, or Holand, to think this way.

Even before the French came, the Menominee associated the area with guilt for another reason. A simplified version was reported in 1637 by a Jesuit who recorded it. A translation: https://books.google.com/books?id=BuzWAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA43

The guilt on the part of the protagonist, and his desire to make restitution, is described in a longer version from 1915:

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Folklore_of_the_Menomini_Indians/0ON3COwVzh0C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22Deluge%22&pg=PA255&printsec=frontcover

As he changes heart, he places some earth to make a new island to live on. The name of the island is not given, but it must be close to the location near Sturgeon Bay mentioned at the beginning.

The wording here does not make it plain as to why he had a change in heart; Was it more about the consequences, or more over grief over actually having done wrong? That it is the former is suggested by the stories following this one, which depict similar, or even worse misdeeds.

It is curious that the center of the lacrosse field would be near Sturgeon Bay. Although it could just be coincidence, the geographical center-line for the northern hemisphere is recognized at Meridian Park. Perhaps they were aware of how the North Star changed in declination as one travels north and south, and from the star’s position they knew that the area near Sturgeon Bay must be central.

Back to the question of which island it is; Conan Eaton, from the Ojibway, reports a different name with a similar definition for Washington Island: https://books.google.com/books?id=s3_hAAAAMAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=Wassekiganeso

But the story doesn’t say that the center of the lacrosse field is on an island. There are multiple places where the geography could match the description.

The two friends, Beaver and Muskrat, died helping to make the island. Presently there are two small islands in Mackaysee Lake, and if the geography hasn’t changed, the remark that “through your kindness we will live here” could indicate Chambers Island. Mahnomah Island, an early name of Chambers Island, would seem to indicate Menominee settlement or at least ownership and use.

However, this 1840 map from a federal surveyor does not show the two islands in Mackaysee Lake, which is drawn, but not labeled. Instead, there is a Makaysee Island (Horseshoe Island). Chambers Island is named Mahnomah Island, even though “Chambers” had previously been used in an 1837 map: https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcwdl.wdl_06769/?r=0.782,0.058,0.113,0.046,0

This map is from https://www.ebay.com/itm/325898145706, and is the best quality copy online. Courtesy of ebay seller valuablethings, it is public domain, because the map is a federal government publication. Lower quality copies are online at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Records_and_Briefs_of_the_United_States/ZB6mE5vIln0C?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=RA3-PA142 and https://www.mwhistory.org/thomas-jefferson-cram-maps-1838-1841/

It is more probable that there is no symbolism at all with the two islands, and instead, the high point with the growing pine tree is Eagle Bluff, and instead of Chambers Island, the new island refers to Horseshoe, or Makaysee Island.

But what does Makaysee or Mackaysee mean? There is nothing online giving the definition. However, Simon Kahquados gave the name and meaning for Gravel Island. It starts in a similar manner, with “mah ko” referring to “Bear”: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Wisconsin_Archeologist/AmxIAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=%22Mah%20ko%20me%20ne%20shine%20me%22

This Ojibwe dictionary has both the same and similar sounding words for “bear”: https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&q=mak&commit=Search&type=ojibwe

The first one in the list, makam, appears to reference the taking of something in the manner of a bear, robbing or clawing it away. That fits with the friends clawing away some earth at the bottom of Green Bay.

The last part of “Makaysee” could be explained by https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&q=cee&commit=Search&type=ojibwe. One meaning of “nisi” is to “get or catch it” for use, which seems related to “shi”, meaning “plus”. Another word for “plus” is “ashi”, which also refers to putting something or someone in a certain place: https://ojibwe.lib.umn.edu/search?utf8=%E2%9C%93&q=ashi&commit=Search&type=ojibwe

If the “sh” became an “s” sound, then Makaysee could mean, “To claw it away and place it.” That would be directly related, but if the name has no relationship to the story, it could just be “Bear catch it”.

Ojibwe is similar to Menominee, and setting this question to rest would require studying books in the Menominee language, which I did not do.

A scholar who compared similar stories from the Great Lakes area concluded that this one was uncommon in that it had not been affected by large revisions which remodeled the narrative: https://books.google.com/books?id=1x_gAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA38

Instead, the differences across the different Indian nations were small, and some could be explained as coming about by accident. Besides these, there is also a story of the Sleeping Bear in Michigan, which is mostly different, but has a a few similarities. Hulda Hollands reported it in 1906, related to her from Chief Wien-da-goo-ish: https://books.google.com/books?id=GKl5AAAAMAAJ&pg=PA210#v=onepage&q&f=false

Although 1906 is a relatively late date, Virgil J. Vogel mentions the dune being designated "L'ours qui dort", French for "the Sleeping Bear" by a 1688 mapmaker, with subsequent references in 1710 and 1721. The 1721 description was later printed in English.

This 1688 map shows L'ours qui dort in the upper right, both Manitou Islands in the middle, and the Door Peninsula and Chambers Island on the left. Courtesy of LIBNOVA, S.L.

The story about the bears does not discuss issues of guilt, rather it is sadness and tragedy. Likewise, some of the other early names did not appear to reference guilt, such as “Kenatao”, meaning “cape”: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Wisconsin_Archeologist/B7QWAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=Kenatao

The question remains about how far the other names go back, and whether any predate the Porte des Morts incident, or colored it.

Kahquados reported the name for Egg Harbor as "Che-bah-ye-sho-da-ning", or "ghost door": https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Wisconsin_Archeologist/AmxIAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22Che+bah+ye+sho+da+ning%22&pg=PA144&printsec=frontcover

This meaning can be confirmed elsewhere. "Che-bah-ye" is "ghost", and this dictionary from the Kansas Heritage Group says that "shkwate'm" is "door". That is fairly close: "shkwa" sounds like "sho-da" and "te'm" sounds like "ning".

The same dictionary lists "cibe'kmuk" as the word for grave, as literally a "body house". Yet "cibe'/Che-bah-ye" also can mean "ghost". It makes sense that if a grave is "ghost house", to get to it, you pass through a "ghost door".

Chambers Island also has a Native American name. Kahquados reported it as Ke-che-mah-ne-do. "Mah-ne-do" is similar to how the Manitou Islands are named Manitou, which means "Great Spirit". It is a different pronunciation, not a different word.

Harriet Martineau in 1837 reported that the Manitou Islands in Michigan were “Sacred Isles of the Indians” because they were said to be the "resort of the spirits of the departed." His explanation is similar to another one, from 1842. James Buckingham recounted how the Manitou Islands in Michigan were considered haunted after an incident where people were killed in their sleep by enemies.

There is a theory that lake islands tended to be of lower usefulness to Indians for game purposes and resources in general, which resulted in some islands at least being visited less often. Today, houses which are rarely entered might develop a rumor for being haunted. But Native Americans designated certain islands which were less frequented as being sacred, such as with the name Manitou. There might also be other reasons, such as what Buckingham described.

The earliest written record which Eaton was aware of for the area's name was from Fr. Emmanuel Crespel. He used "Cap a la Mort" in 1728. He used it in a manner which implied that the name was already generally known by others. "Cap" is "cape", and "a la" means "to the", with "a la Mort" being a French idiom for someone who is mortally ill or fatally wounded.

That Egg Harbor opens to Chambers Island implies that the island must be the ghost house, with Egg Harbor being the door, or gateway to Chambers Island. And to think of it, the act of passing through a "ghost door" is to die, which sounds a lot like Emmanuel Crespel's use of "a la Mort" with his name for the peninsula.

The implication is that "Cap a la Mort" could be a reference to Egg Harbor being the ghost door, rather than a reference to the Porte des Morts battle. If the peninsula was named for Egg Harbor, then it was thought of as the "cape where the ghost door is located".

In this case, the designation of the water passage as Porte des Morts would have been a newer name which referenced either "Cap a la Mort", the Egg Harbor "ghost door", or both. Porte des Morts directly refers to a deadly incident, the uncertain nature of which is described with detail by Eaton in his "The Naming: A Part of the History of Washington Island".

On an 1839 map, the name of the passage is used for the peninsula: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3700m.gct00185/?sp=15&r=0.472,0.209,0.067,0.043,0

In 1848, a lighthouse was designated for “Port du Mort”, now Pilot Island: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Public_Statutes_at_Large_of_the_Unit/OkznN-Whd7sC?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=%22Port%20du%20Mort%22

With “Port du Mort” as the name of the lighthouse, the use in print would have familiarized it.

In 1851, the water passage at the end of the peninsula is termed “the Door” by the state legislature, while the peninsula itself is just called “Peninsula”:

https://www.google.com/books/edition/Wisconsin_Session_Laws/T-IqAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=%22door%22

Also that year, an act creating Door County was passed, but it doesn’t explain the name: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Wisconsin_Session_Laws/T-IqAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=RA2-PA50&printsec=frontcover

The use of “Door Peninsula” and “Door County Peninsula” coincided after 1851. “Door County Peninsula” was used in both formal and informal contexts.

The impression I get is that people using “Door County Peninsula” were referring to a peninsula which didn’t yet have a commonly known name, and they were borrowing the county’s name to make up for it. It seems that by naming the county, the state legislature inadvertently ended up naming the peninsula.

So what is the significance of this? That the name goes back to the French use for the water passage way links the county’s name directly to the tradition of the Porte des Morts battle. Both from the context of the tragedy and the deluge story, the implications of guilt were accepted and understood by Native Americans, and were reiterated by what happened at Porte des Morts.

The naming of Porte des Morts or Porte du Morts was not unfair to the Indians, since they reflected on guilt at times even without influence from the French. Holand’s description of arrogance is also fitting, since it describes an attitude unheedful to danger.

The meaning of Door County’s name incorporates a warning not to be taken in by les portes de la mort. Hopefully it will be possible to avoid the sort of situation the Israelites were prophesied to fall into, which was described in Jeremiah 9: https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Jeremiah+9&version=KJV

Door County surely has other true meanings to people, but it would be arrogance to be above ever needing a warning about les portes de la mort.

Posts relating to history

https://doorcounty.substack.com/t/history